Many thanks to the Boston Globe Travel section for running this story on Sunday, July 18 on If We Knew then What We Know Now about #vanlife camping in the wild. Hope you enjoy:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/07/14/lifestyle/sleep-anywhere-van-think-again/

TRAVEL

Sleep anywhere in a van? Think again

We learned the hard way that you can’t just wing it when you’re trying to find a place to park your RV for the night. Here are some tips we learned along the way.

By Sue Hertz Globe correspondent,Updated July 14, 2021, 12:00 p.m.

The woman with the broad face by the door at the Kayenta, Ariz., Chevron station smiled ever-so-slightly. “Camping?” she said, pointing up the highway from where we had just driven in our rented camper van. “Utah. Or maybe the Grand Canyon.”

What she didn’t say was: “Idiot. There is no camping on tribal lands.” And tribal lands — Navajo and Hopi country — is where we’d travel for the next few hours into darkness.

Instagram paints #vanlife camping in a romantic hue. Wake up by a mountain stream, a California beach, a field of wildflowers. Vanlifers rave about the freedom of pulling over anywhere. What they neglect to add is that finding those glorious, and even not-so-glorious, spots requires research, the right apps, and people. Hard copy maps are also a plus.

Had I done a little legwork, I would have known that we would not find a welcome mat between Monument Valley and the Grand Canyon, our destination for the next day. I would have known that as I punched my camping apps while the Chevron woman watched, that the site I chose may have been 30 minutes from the Grand Canyon, but it was also on the other side of the Delaware-size natural wonder. Four hours away. We were less than a week into our monthlong #vanlife tour of the West, and this was our first stab at camping without a reservation. Parked in the Chevron lot, we wondered how anyone found campsites off the grid.

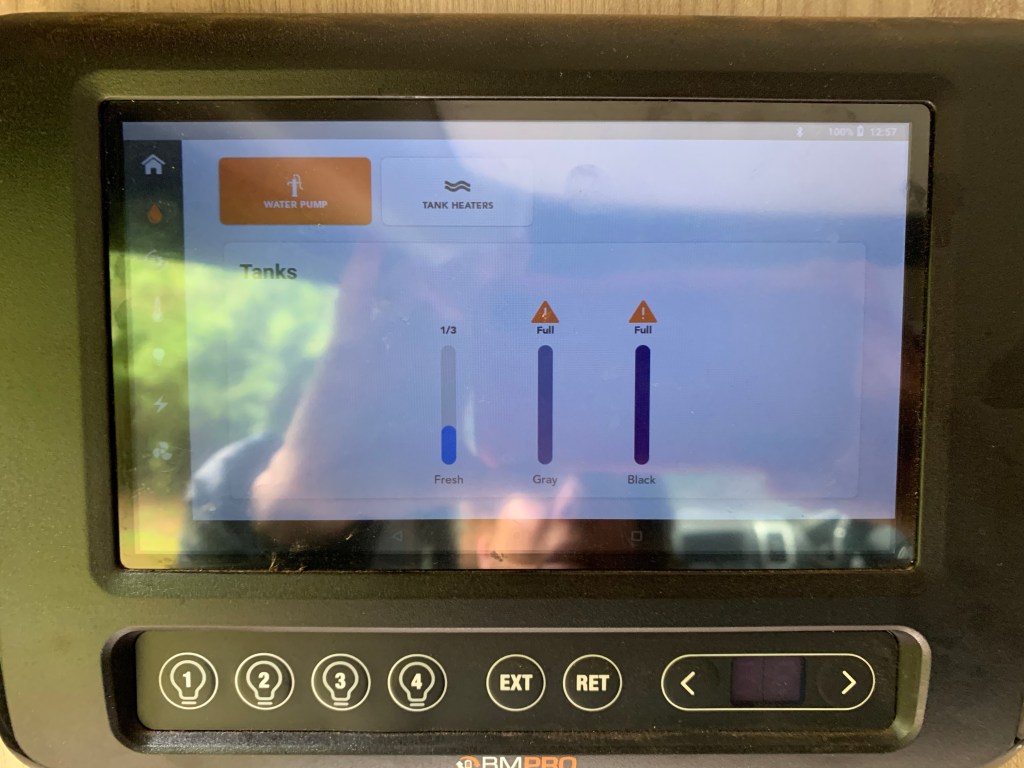

But they do, and now after a safe return and many happy nights camped in the wild, we have some suggestions for the 56 million North Americans who, according to the RV Industry Association, plan to vacation this summer in everything from teardrop trailers to bus-size motorhomes to Ford vans that they own, rent, or borrow. To be sure, many, especially first-timers, will feel more secure with reservations at official campgrounds, such as KOA. Official campgrounds, after all, provide amenities, ranging from toilets and showers to dog parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and laundromats. Some will have dumping stations for rigs to fill the fresh water and deplete the gray (sink/shower) and black (toilet) water tanks.

But as legions of families, couples, and solo adventurers break out of their COVID bubbles in the next four months, available designated campsites may prove elusive. And that’s where boondocking, or dispersed camping, or whatever you want to call free camping comes in. In some cases, the most luxury you’ll find is a vault toilet, but most often you’ll perch on land with nothing but the wind. You are expected to pack in and out all of your stuff, to leave no trace — no beer cans, no toilet paper, no food scraps. You are expected to bury all human and pet waste six inches deep and 200 feet away from any water source, and to extinguish all fires. Without a staff to protect and maintain these wilderness sites, campers are responsible. A small price to pay for a night by a stream with only Redwoods for company.

Where to camp for free, or perhaps a small fee

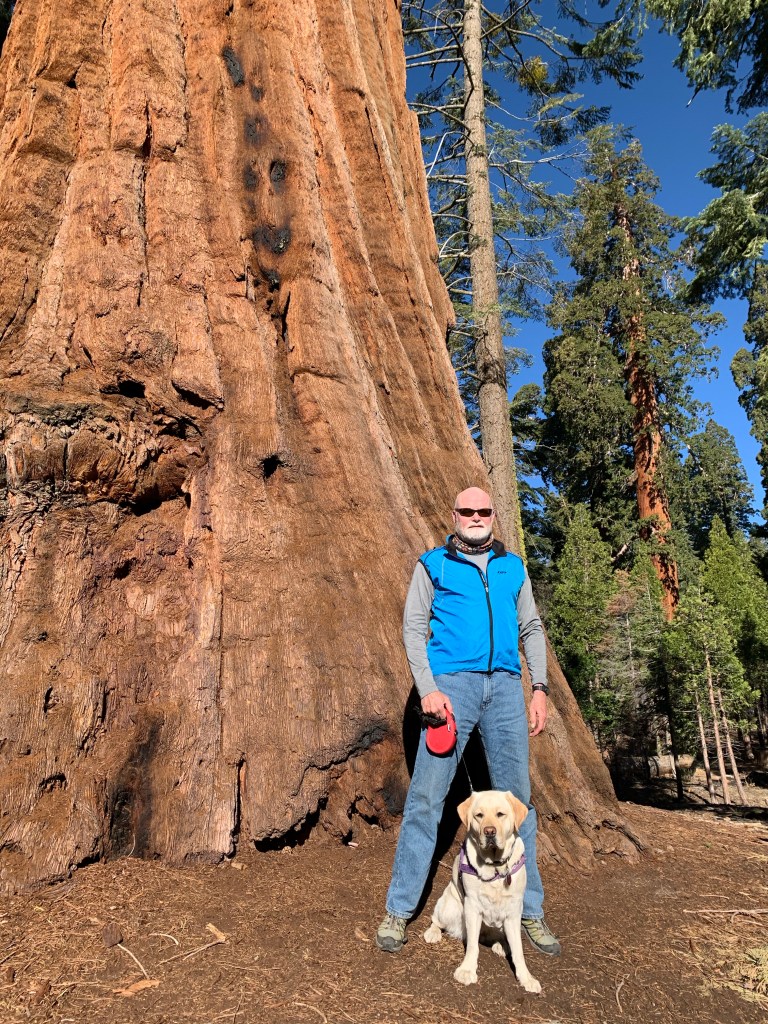

Public lands. When we talk about dispersed camping on public lands, we do not mean national parks. If a national park allows backcountry camping — and many do not — it is tent only. The public lands most hospitable to parking your rig overnight are woods and fields operated by the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management. The difference between the two organizations is a little confusing since many of the kinds of land they oversee overlap, but suffice to say both are under federal jurisdiction and are supported by your tax dollars. Although there are scattered sites around the Midwest and East Coast, most USFS and BLM land hospitable to overnight free camping are in the West. USFS or BLM camping is often found on secondary roads, and include remote sites in the woods or on a field, or perhaps by the side of the road. There are no amenities. No picnic tables. No fire pits. No toilets. A 14-day stay is usually the maximum allowed. Our favorite stay was a wooded site deep in the Sequoia National Forest that we found by driving on a rural road in search of the Trail of 100 Giants, a grove of the massive trees.

Parking lots. Walmart. Bass Pro Shop. Cabela’s. All are reputed to be friendly to RV and van overnight camping. But not all parking lots are created equal, and some stores do not want your rig on their property after hours. Best to call ahead. In our case, the Bass Pro manager said that overnight camping was once welcome on her central California asphalt, but then Bass Pro sold the parking lot to the neighboring movie theatre. Still, she said, she sees plenty of Jaycos and Sprinter vans setting up for the night. “So I should ask for forgiveness rather than permission?” I asked. She laughed. “I’m not saying yes,” she said. “But I’m not saying no.” Despite a flock of quacking geese in the mall’s pond, our night in the Bass Pro lot was uneventful, if bright from overhead lights. Security drove by at 1 a.m. but didn’t stop. We drove off just as the morning crew arrived to pick up outside litter.

Neighborhoods. Like parking lots, not all neighborhoods embrace camper vans and Winnebagos lining their sidewalks. Yet floating between residential streets is a common strategy among vanlifers. The key is to find neighborhoods in which a large vehicle with out-of-state plates will not attract attention and to not overstay your welcome. We spent one night on a side street in Manhattan Beach, Calif., behind Son #2′s apartment. A little uncomfortable — we were on a slight incline — but neighbors didn’t complain or call the police. We were lucky. Anyone who has pulled up into an empty public spot fears The Knock. Two women we met in Wyoming had successfully boondocked in their Travato in Key West, until they didn’t. On their second night in a marina, the police rapped on their door, and told them to move on. One night was fine, but no lingerers.

Harvest Hosts: Technically, by joining Harvest Hosts for the annual fee of $99, you can book a free dry camping (no amenities, including water or toilets) at any of the 2005 host farms, wineries, or breweries. To be fair to these businesses, and thank them for providing shelter, you are expected to purchase something that they sell. We had looked forward to camping at a winery or farm on our tour of the West, but didn’t connect to any, partially because often there weren’t options on our routes, and mostly because if there were, we were too spontaneous to book ahead. Of the many campers we met who had stayed with a Harvest Host, the reviews were positive. The sites are often not scenic — just the parking lot — but you can sleep without fear of The Knock — and you can depart with some nice bottles of Sauvignon Blanc.

How to find these sites:

Apps. No shortage of digital help tucked into your phone.

General camping apps, such as The Dyrt , Freecampsites,orCampendium, are great for identifying all kinds of potential campsites — public, private, designated, or dispersed, fee or free — across the country.

Other apps are more specific. The USFS & BLM Campgrounds app, for instance, focuses on camping options under the jurisdiction of the two organizations. Freeroam focuses on only BLM sites.

Harvest Hosts app shows all of its hosts and allows you to book (and cancel). Recreation.gov lists all of the country’s federal campgrounds, many of which are in national monuments and forests. Most require a nominal fee, but fees are oh-so reasonable, especially if you have any kind of national park pass.

HipCamp is another app that doesn’t focus on free camping, but inexpensive options. Like Airbnb, it connects property owners willing to share their turf with campers. HipCamp options range from one site with no amenities on a ranch to 20 spots with water, perhaps even a vault toilet, on farmland. And you must book ahead, even if it is last minute. We enjoyed our HipCamp site just outside of Blanding, Utah, on a field with room for nine other campers, on a quiet road that led to a natural bridge and a pueblo.

Maps

On our second-to-last day of #vanlife, a USFS ranger in Jackson Hole, Wyo., gave me a hard copy map of all the public land in Wyoming and what was allowed in each, from hiking to fishing to camping. Had we acquired such a map — which can be found at ranger’s stations, information centers, even gas stations — for each state visited, our search for free or inexpensive shelter would have been so much easier. Thanks to the Wyoming map, we spent our last night on the road in a blissfully peaceful spot on the Platte River, surrounded by canyons.

People

Park rangers are your friends. They can tell you where to camp, and how long you can camp. Visitor information greeters are gold. In hopping Sedona, Ariz., home to boutiques and bars and patio restaurants, the woman behind the desk at the visitor info storefront didn’t hesitate to direct us out of the congested downtown south on Route 89A to the 525, a National Forest fire road. Surrounded by acres of cactus and yucca plants, we snagged a site for the night, the silence interrupted only by the occasional rumble of a Subaru or pop-up camper seeking a spot to call home.

Fellow campers, too, are key sources. In Denver, our #vanlife starting point, Son #1 shared a pin drop on a Google map of a national forest outside of the Grand Canyon with free camping. We didn’t think much about it, until we were en route to the national wonder at 5 p.m. with hours to go before we would arrive at the campsite I had booked in the Chevron station parking lot. “Look!” I said to my husband, Bill, who was driving and didn’t want to look at the map on my phone. “Luke’s camping spot is only 15 minutes away.”

Bill was unsure. He preferred the certainty of a reservation. But since the pin point was on the way, he agreed. And just off Route 64 was the Kaibab National Forest and the fire road where our Denver-based son had camped the summer before. On this late April night, the only other campers were in an old school bus parked off in a field. We slept well, and when we awoke, we could see the outline of the Grand Canyon looming against the sapphire sky.